Under-representation of women in leadership: The need for cultural change action

Leadership#BreaktheBias#GuestArticle

“Gender appears to be at the forefront of the global humanitarian agenda”. So wrote the editors of the esteemed Academy of Management Journal in 2015, when reviewing nearly sixty years of research on gender issues in management. Despite setbacks to women’s rights around the world since the date of that paper, we believe that gender equality in business, and specifically leadership, is still one of the dominant themes in organisational development (along with diversity in general). If it isn’t dominant in your organisation, it surely should be.

Ratios of women in senior leadership across regions are reported at: Africa 38%; Eastern Europe 35%; Latin America 33%; European Union 30%; North America 29%; and Asia Pacific 27%. A sobering set of statistics. Globally, the ratio of women leaders going up the ladder decreases: support staff 47%; professionals 42%; Managers 37%; senior managers 29%; executives 23%. The very low rates of women CEOs before the COVID-19 pandemic has become even lower, now at 5%. All this is despite the evidence that higher performing organisations have higher ratios of women to men in leadership roles. (So much for capitalism optimising performance.)

Various theories on the lack of women leaders have developed over the years, including individual-centred factors such as a comparative lack of confidence in women compared to men, lack of willingness to self-promote, and reluctance to give honest assessments of their performance. More organisation-centric perspectives suggest that women receive insufficient development, gender differences between men and women play a role, and anti-woman bias predicates against progression. Many of these factors are created by, or reinforced through, systemic and process aspects of organisations. Not surprising, since the organisations themselves are reflective of the wider societies in which they exist – a jumble of systems and processes of human life. Michelle Bligh and Ai Ito conceptualise this as the Male Competitive Model. They say that “cross-culturally, most modern organisations have been developed and led by men in a way that has been adapted to their values and assumptions in predominantly gender-segregated societies”.

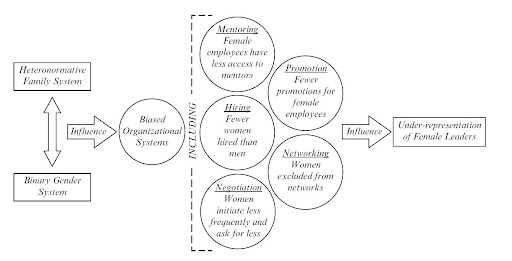

Figure 1 shows how these influences affect the under-representation of women in leadership. Amy Diehl and Leanne Dzubinski have identified twenty seven gender-based leadership barriers at different levels of society.

Figure 1: Sociocultural and organisational systems affecting the under-representation of women leaders (Michelle Bligh & Ai Ito, in the Handbook of research on gender and leadership, 2017, page 289)

Perhaps a useful starting point for organisational leaders, is to reflect on findings from two recent business performance reports. Where women are in top leadership positions, businesses have: improved financial performance; strengthened organisational climates; increased corporate social responsibility and reputation; talent leveraged better; and innovation and collective intelligence are enhanced. The ethical and moral case for equal ratios of women and men in leadership is indisputable – so is the business case.

The next step is to acknowledge and accept that culturally-driven norms will only change when those norms are challenged and cultural change is defined, planned for, and enacted. Not simply for the business performance improvements it brings, but quite clearly, also, for ethical and moral reasons. Lack of women leaders is culturally-driven and needs cultural change action to bring more and more women leaders to the upper echelons of organisations. This leads, inexorably, to such change actions as women-only leadership development, women mentors for (future) women leaders, and revised metrics for performance (e.g. metrics that acknowledge the ‘soft’ power that women deploy to great effect, but which is not currently measured).

The motivating forces for this change must include men – they currently have most leadership roles, from which they can support this work. Men must join with and fully support women when they initiate the work to bring equality for women leaders. There is even greater emphasis on this now as the world emerges slowly from the COVID-19 pandemic and we find not more, but fewer women in senior leadership roles.

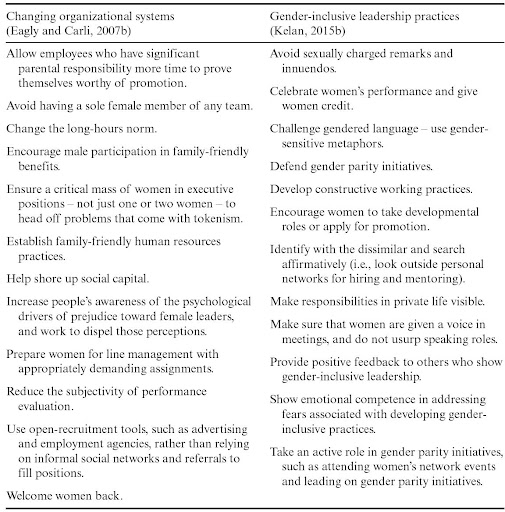

We finish off this article with a list of cultural change actions that organisations can work with, Figure 2, again by Michelle Bligh and Ai Ito. What we must also ask is: what is needed to bring about these changes? The answer is for senior leaders to have the vision, courage, and personal commitment to drive cultural change programs into their organisations. This means personally sponsoring prioritised, fully funded, fully resourced change programs to achieve equality for women at all levels of leadership. It also means being prepared to be seen, in wider society, to be passionate and engaged in the issue of equality for women.

Figure 2: Solutions for changing organisational systems and practices (source: Michelle Bligh & Ai Ito, in the Handbook of research on gender and leadership, 2017, page 298.)